Our Name

Our dormitory bears the names of siblings Hans and Sophie Scholl, who were part of the "White Rose" circle. The "White Rose" was a student resistance group in Munich that fought against the Hitler regime during World War II.

Hans and Sophie Scholl, along with five comrades - Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber, Willi Graf, and Hans Leipelt - paid for their brave resistance with their lives. Several other friends were sentenced to lengthy prison terms.

The name of the dormitory should always remind everyone of the courageous example set by the Scholl siblings and their friends from the resistance group "White Rose", urging everyone, everywhere in the world, to stand up for freedom, peace, and human rights - just as they did.

The Scholl siblings

Hans and Sophie Scholl were two of the six children of Robert and Magdalena Scholl. The parents were liberal-minded; father Robert was a pacifist, and mother Magdalena was deeply religious. They set an example for their children to stand up for their convictions. The upbringing based on Christian-liberal values likely had a significant influence on why the children rejected the Nazi regime. Like their older siblings Inge and Hans, initially, Sophie was also enthusiastic about the communal ideals propagated by the National Socialists. The Scholl children were initially involved in the Hitler Youth (HJ) and the League of German Girls (BDM), although initially, they held a somewhat positive view towards both. This caused frequent disputes within the family.

Later on, the children increasingly discovered contradictions between the party-controlled imposition by the National Socialists and their own liberal thinking. In the HJ and the BDM, the Scholl siblings subsequently caused conflicts that cost them their leadership positions.

The Scholl siblings, especially Sophie, and their friends were influenced by the works of the Catholic publicist Theodor Haecker, who was no longer allowed to publish under the Nazi regime. In their circle of friends, they frequently discussed the progressive works of the publicist Carl Muth and Theodor Haecker, as well as the lectures of the nonconformist philosophy professor Kurt Huber.

Until their arrest, Hans and Sophie were studying at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU). Hans studied medicine starting in 1939, while Sophie studied biology and philosophy from 1942. Due to their medical studies, Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, and their friends were deployed as medics on the war front. As “medical assistants”, these young medical students were immediately confronted with the brutal reality of war, an experience that deeply affected and shaped them.

The „White Rose”

The “White Rose” was a resistance group formed by students emerging from the Catholic and bündisch youth movements against the National Socialist Hitler regime. Starting in the summer of 1942, they distributed leaflets in Munich against the Nazi dictatorship and calling for an end to the war. Hans and Sophie Scholl were part of the inner circle of the White Rose, alongside Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell, Kurt Huber, Willi Graf, and Hans Leipelt. Over time, helpers from other German cities also joined the resistance group. Even the philosophy professor Kurt Huber, who taught at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, became another like-minded individual and joined the resistance group in the summer of 1942.

The Leaflets of the White Rose

Due to the suppression of opinions by the Hitler regime, the university no longer provided space for open and critical conversations. Intellectual debates could only take place in protected and private environments. Therefore, the “White Rose” circle held private reading evenings where they initially read books forbidden by the Nazi regime and discussed them. In July 1942, the group felt the need to take action. Hans Scholl and Alexander Schmorell began secretly writing and distributing four leaflets under the title “Flugblätter der Weißen Rose” (Leaflets of the White Rose).

Through helpful friends in other cities – Ulm, Stuttgart, Freiburg, Saarbrücken, Hamburg, and Berlin – the leaflets of the “White Rose” were secretly distributed.

However, possession and distribution of anti-regime leaflets were strictly prohibited in Nazi Germany. Citizens were obligated to surrender such writings to the police. The first leaflets were reported by about a third of the approximately 100 recipients.

Upon their return from medical service in Russia, Alexander Schmorell and Hans Scholl were even more determined to resist. Now, Sophie Scholl, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and at the end of December 1942, Kurt Huber also actively joined.

In January 1943, the Battle of Stalingrad ended, later proving to be a turning point in World War II, with a catastrophic defeat for the German Wehrmacht. Of the original 330,000 soldiers of the 6th Army, more than two-thirds had fallen. On the Russian side, over a million people died in and around Stalingrad.

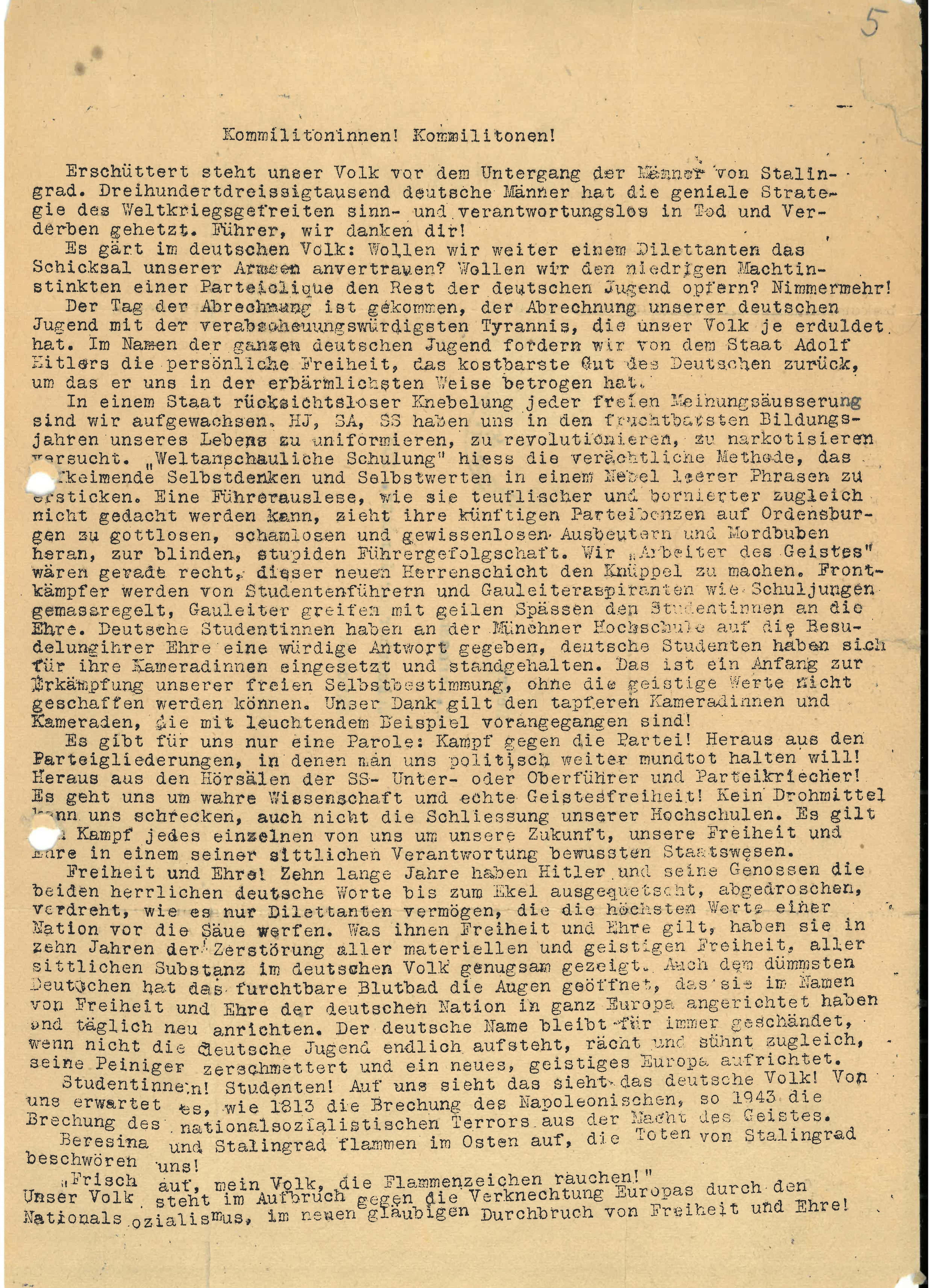

For the resistance group “White Rose”, this served as the impetus for their fifth and sixth leaflets, which they collectively drafted in January and February 1943, now under the pseudonym “Wiederstandsbewegung in Deutschland” (Resistance Movement in Germany). Using a new duplicating machine, they produced about 6,000 copies each. During the war, paper, envelopes, and stamps were rationed; the purchase of larger quantities made the buyer suspicious. By producing and distributing the leaflets, the students were risking their lives.

However, the resistance group not only attempted to defy the Hitler regime with leaflets. Hans Scholl, Willi Graf, and Alexander Schmorell spent several nights in February 1943 using tar paint to write the slogans “Nieder mit Hitler” (Down with Hitler) and “Freiheit” (Freedom) on the walls of their university and other buildings.

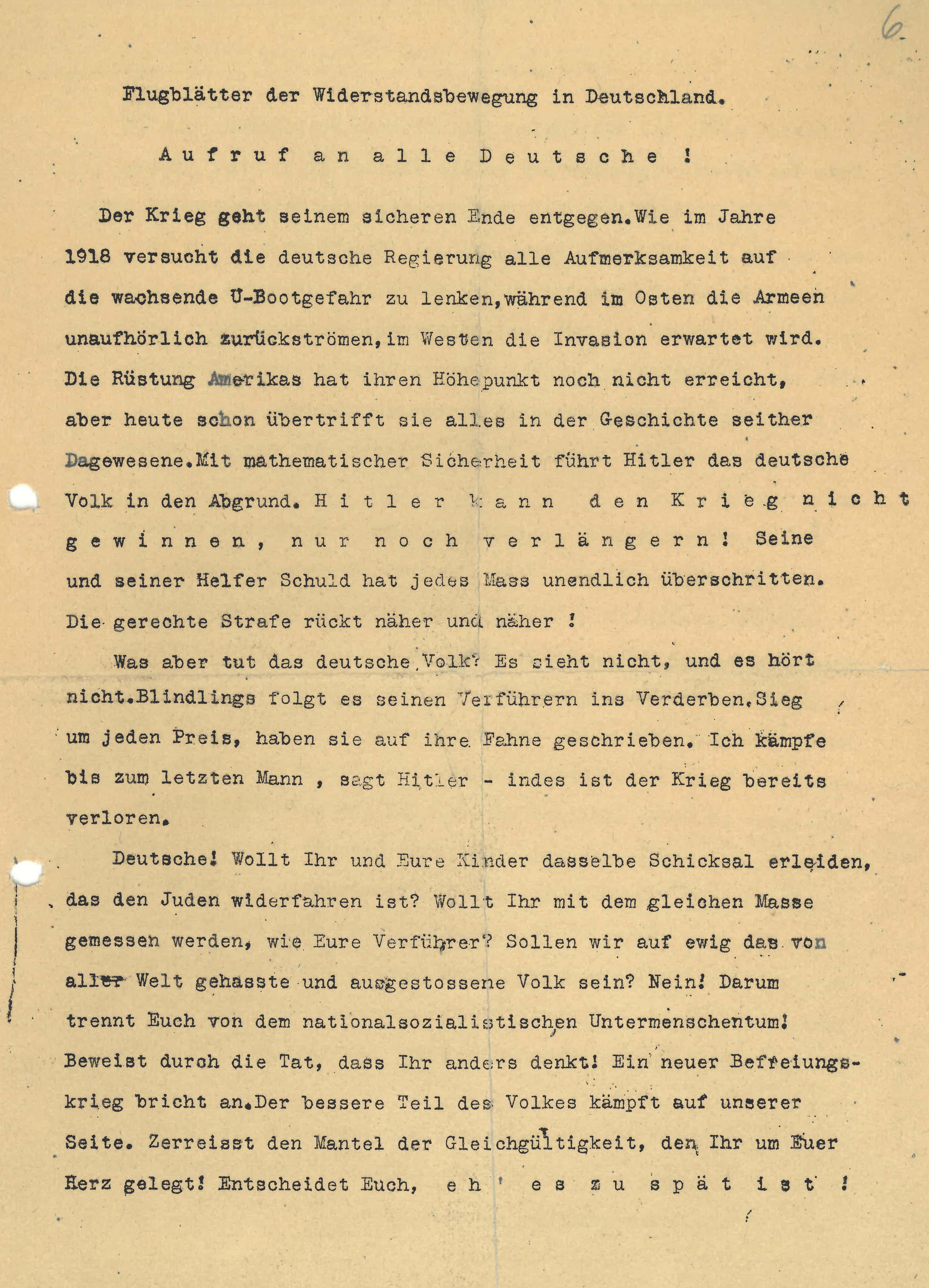

down left and center: the fifth leaflet of the resistance group „Widerstandsbewegung in Deutschland” BArch, R 3018 _/_ 18431

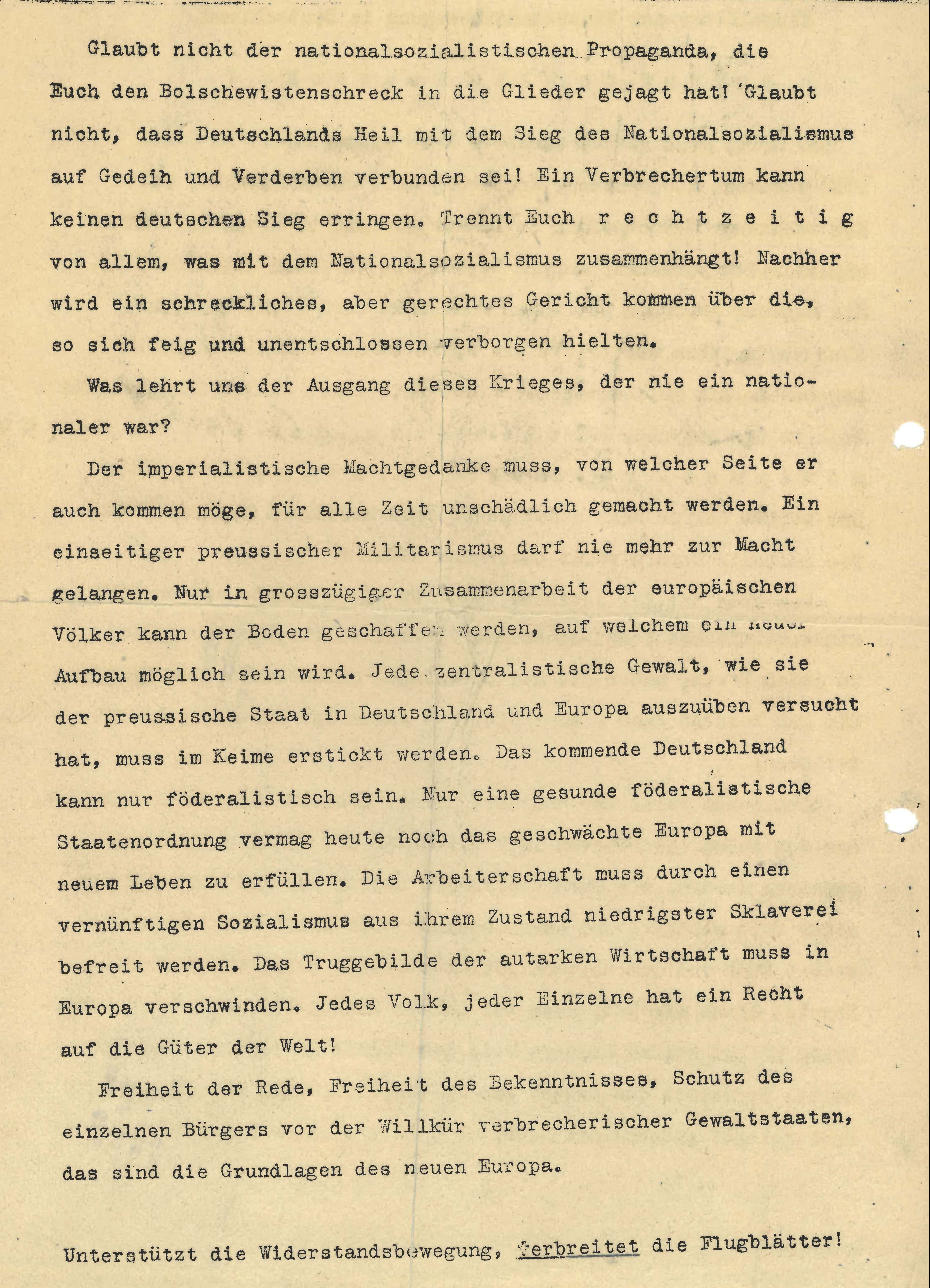

down right: the sixth leaflet of the resistance group „Widerstandsbewegung in Deutschland” BArch, R 3018_ / _18431

below: the fifth leaflet of the resistance group „Widerstandsbewegung in Deutschland” BArch, R 3018 _/_ 18431

below: the sixth leaflet of the resistance group „Widerstandsbewegung in Deutschland” BArch, R 3018_ / _18431

Arrests, show trials and death sentences

On February 18, 1943, around 11 o’clock, the Scholl siblings placed the sixth leaflet in front of the lecture halls in the main building of the LMU, dropping the remaining leaflets in the atrium. They were observed and apprehended by the caretaker, Jakob Schmid. Both were immediately arrested by the Gestapo. Among Hans Scholl’s possessions, the police found a handwritten leaflet draft torn into small pieces by Christoph Probst, who was subsequently arrested the following day.

Sophie and Hans Scholl were interrogated separately. Sophie confessed to wanting “nothing to do with National Socialism”. When she was informed during the interrogation the next day, on February 19, 1943, at four in the morning, that her brother had confessed, she also admitted guilt.

Roland Freisler, the infamous President of the so-called People’s Court, hurried from Berlin to swiftly conduct proceedings with the detainees on February 22, 1943. Hans and Sophie Scholl, along with Christoph Probst, were sentenced to death and executed on the same day at the Munich-Stadelheim prison by the guillotine. At the scaffold, Hans Scholl loudly exclaimed, “Es lebe die Freiheit” (Long live freedom).

Just a few days after the arrest of the Scholl siblings, Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were also detained. In the second trial of the People’s Court against the ‘White Rose’ on April 19, 1943, they were sentenced to death. Kurt Huber courageously opposed “Hitler’s hangman”, Roland Freisler, during the trial, who denied him any honorable motives. On July 13, 1943, Kurt Huber and Alexander Schmorell were executed, while Willi Graf was executed on October 12, 1943, after the Gestapo unsuccessfully tried to extract information about his connections to other regime opponents.

By the end of February 1943, the Munich circle of friends had mostly been imprisoned. Their family members were placed in “Sippenhaft” (kinship detention) on Heinrich Himmler’s orders.

In the second trial on April 19, 1943, in Munich, eleven more individuals were accused of aiding in the distribution of the leaflets. Most of these defendants received lengthy prison sentences. On July 13, 1943, a third trial took place in Munich against four defendants, followed by a fourth on April 3, 1944, in Saarbrücken against one defendant. A fifth and final trial occurred on October 13, 1944, in Donauwörth against seven defendants, one of whom, Hans Leipelt, was sentenced to death and executed on January 29, 1945, in Munich-Stadelheim by beheading.

What was the purpose of the group?

With the “Leaflets of the White Rose” (1st to 4th leaflets), the “Leaflets of the Resistance Movement in Germany” (5th and 6th leaflets), and with the wall slogans, the resistance group aimed to mobilize the academic youth and, beyond that, all well-intentioned Germans against the criminal Hitler dictatorship. They did not achieve this goal, yet their sacrifices were not in vain. They continue to be shining examples of how, even in the darkest times, people can bravely and selflessly stand up for freedom and peace.

Winston Churchill, British Prime Minister during World War II, said the following about the “White Rose” in 1946:

„In Germany, there existed an opposition that belongs to the noblest and greatest in the political history of nations. These people fought without help from within or without—solely driven by the unrest of their conscience. As long as they lived, they were invisible to us because they had to disguise themselves. But through the dead, the resistance became visible. These dead cannot justify everything that happened in Germany. However, their deeds and sacrifices are the indestructible foundation of the new construction.“

Further reading

More information and background research on the resistance group “White Rose” can be found on the following websites:

White Rose Foundation e.V.:

https://www.weisse-rose-stiftung.de/widerstandsgruppe-weisse-rose/

Federal Agency for Civic Education::

https://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/weisse-rose/60941/vorwort

Or in the following literature:

Die Weiße Rose

Published by the White Rose Foundation, Gentner Straße 13, 80805 Munich, 3rd edition. This brochure (87 pages), available in several languages, can also be obtained at the White Rose Memorial site next to the atrium of the University of Munich.

Barbara Beuys, Sophie Scholl- Biographie, insel Taschenbuch 4049, Berlin 2011

ISBN: 978-3-458-35749-0

Barbara Leisner, „Ich würde es genauso wieder machen“ Sophie Scholl

List Taschenbuch Verlag, 3. Auflage, 2000, ISBN 3-612-65059-9

Rudolf Lill (Hrsg.), Hochverrat ? Neue Forschungen zur Weißen Rose

Portraits des Widerstands, 1. Auflage 1993, Veränderte Auflage 1999,

UVK Universitätsverlag Konstanz GmbH, Konstanz 1999

ISSN 0943-903 X, ISBN 3-87940-634-0

Inge Scholl, Die Weiße Rose

Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 9. Auflage, 2001, ISBN 3-596-11802-6

Hermann Vinke, Das kurze Leben der Sophie Scholl

Ravensburger Verlag, Erstauflage: 1986, ISBN: 3-473-54208-3